|

|

|

|

|

|

911 – A PHOTO

ESSAY OF GROUND ZERO

by Karl

Haupt

copyright

© Karl Haupt 2001

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

September 13th, 2001

This

photography series includes over 250 images. These photos are mainly long

exposures only lit by the emergency floodlights of the search-and-rescue teams

at the WTC site. A rising wind on the 13th of September made it

possible for the first time to photograph the disaster within the immediate

vicinity. During that night, the excavation

work stopped for the first time due to a suspected gas leak, which allowed

specialists to listen for possibly trapped survivors underneath the wreckage -

after two days of frantic digging.

Photo

Gallery

Press Review

The Daily Star

Photographer focuses on ground zero in NYC

By Jill Fahy

ONEONTA - Karl Haupt said he was out to capture the surreal atmosphere

of ground zero when he took a 35 mm camera and about 30 rolls of film to the

site and began shooting. It was Sept. 13, two days after the

Haupt, of Oneonta and

Shot at night, the images, titled "Commemoration

"It looks like another place and another time," said a woman

who attended Wednesday's program. "It's not real."

Haupt said it wasn't easy to get close to ground zero. It helped that he

took only a camera and film, not the usual cumbersome equipment that

accompanies the professional photographer. As he shot he could feel the heat

radiating from the pile of welds, pressed steel and concrete. "It was one

of the first impressions I got."

Another impression, he said, was the scale of the destruction and the

resiliency of the now-famous, recognizable section of trade center scaffolding.

A photographer who has spent time in war-torn Sarajevo, Haupt said what

he saw in New York that night was far worse.

"It doesn't measure up at all," said Haupt of his war-time

assignments. "This is incredible in terms of destruction... "I've

seen the images taken during World War II, after the Allied bombings where you

could see structures that were destroyed but still recognize them as what they

were. With this, there was no way of even defining what structures they could

have been.

Press Review

Rhein-Neckar-Zeitung

Heidelberg,

Germany

Mittwoch, 29. Januar 2003

Metaphysische

Dimension der Gewalt

Das

Heidelberger DAI zeigt Fotografien von Karl Haupt -

Von Milan

Chlumsky

In

der Nacht vom 13. September 2001 - zwei Tage nach der Attacke auf das World

Trade Center in New York - gelang es dem in New York geborenen und in Köln

lebenden Fotografen Karl Haupt, die Absperrungen um die eingestürzten Türme zu

überwinden. Heimlich und behutsam begann er die Trümmerlandschaft zu

fotografieren, die inzwischen auf Tausenden von Metern fotografischen Materials

festgehalten wurde und deren prägnanteste Momentaufnahmen um die Welt gingen.

Fast

jeder Schritt bei der Aufräumung des Schutts, der nach dieser Katastrophe übrig

blieb, wurde dokumentiert und in Ausstellungen rund um den Globus präsentiert.

In

vielen Fällen wurden jene heroischen Momente gewählt, die den Einsatz

unzähliger Feuerwehrleute und freiwilliger Helfer dokumentieren. Nur wenige

Fotografen haben zu jener Stunde realisiert, dass es sich nicht nur um einen

Terroranschlag auf das Hauptquartier des Kapitalismus handelte, der mit

tatkräftiger Medienhilfe auch entsprechend visualisiert wurde, sondern dass

es daneben darum ging, die westliche Welt mit einem Schlag in einen Untergang  biblischen

Ausmaßes hineinzureißen.

biblischen

Ausmaßes hineinzureißen.

Dieses

diffuse Gefühl, dass es neben der rein materiellen Zerstörung auch um die

Zerstörung sämtlicher Werte ging, die das Nebeneinander von verschiedenen

Zivilisationen (und Religionen) ermöglichte, kristallisierte sich nach und nach

zu einem Kampf gegen den globalen Terrorismus. Das Ursprüngliche an dieser

Empfindung konnte jedoch - fotografisch gesehen - nur in einem einzigen Modus

wiedergegeben werden: durch gleichzeitige Nähe und Distanz, durch das bewusste

Weglassen alles Heroischen und durch die genaueste Fixierung eines Zustandes im

Ringen zwischen Leben und Tod, der sich womöglich immer noch in den vor der

Kameralinse befindlichen Trümmern abspielte.

Eine

der von Karl Haupt im Heidelberger Deutsch-Amerikanischen Institut zu sehenden

großformatigen Farbaufnahmen des WTC zeigt eine noch lodernde Feuerquelle. Die

Flammen erleuchten auf ähnliche Art und Weise die gespenstische Szenerie, wie

es etwa William Turner in seinem Bild des brennenden "House of Lords"

in London festgehalten hat. Nicht um Details ging es in diesem Bild, sondern um

die - durch eine genaue Lichtregie - Wiedergabe der zerstörerischen Kraft, die

aus einer realen Feuersbrunst eine symbolische machte. Diese und andere

Zerstörungen prägen schließlich die Psyche der Menschen und verursachen, wenn

nicht Psychosen, so doch Albträume.

Das

fotografische Essay von Karl Haupt mit dem Titel "911 - A Photo Essay of

Ground Zero" schreitet entlang dieses subtilen Grats zwischen dem

"Symbolisch-Apokalyptischen", wie man es etwa aus der Malerei kennt,

und der notwendigen Distanziertheit, die umso prägnanter die Stelle nach dem

Zusammenbruch, die unvorstellbare Menge an Leid und die schwindende Hoffnung

ins Bildzentrum rückt.

Dieses

aus schwarz-weißen und aus fast monochrom wirkenden Farbaufnahmen bestehendes

Essay ist zweifelsohne eine der besten fotografischen Dokumentationen über die

Katastrophe in New York, da sie explizit jene metaphysische Ebene der

Zerstörungswut berücksichtigt, die man hauptsächlich den antiken Mythen

zuschrieb und nur als vage Drohung in manchen biblischen Geschichten verspürte.

In Karl Haupts Essay ist diese metaphysische Ebene sichtbar.

"911-

A Photo Essay of Ground Zero", DAI Heidelberg, bis 13. Februar.

-->

translation of above

Press Review

Rhein-Neckar-Zeitung

Wednesday, 29th January, 2003

Metaphysical

Dimensions of Violence

The

German-American Institute

By

During the night of September 13th, 2001 - two days after the

attacks on the

Besides the purely material destruction, there is a diffuse sense that

this was a destruction of all those values that allowed the co-existence of  different civilizations (and religions) - which crystallized by and by

into a war against global terrorism. The root of this notion could only be

shown -at least in a photographic sense - in one particular way: through simultaneous

closeness and distance, by leaving out all the heroics and by capturing a

condition locked in a struggle between life and death, a struggle that possibly

was still taking place in front of the camera lens, underneath the ruins.

different civilizations (and religions) - which crystallized by and by

into a war against global terrorism. The root of this notion could only be

shown -at least in a photographic sense - in one particular way: through simultaneous

closeness and distance, by leaving out all the heroics and by capturing a

condition locked in a struggle between life and death, a struggle that possibly

was still taking place in front of the camera lens, underneath the ruins.

One of Karl Haupt's large-scale color photos shown at the Heidelberg

German-American Institute depicts a still blazing conflagration. The flames

illuminate the eerie scene similar to perhaps the way William Turner captured

the burning "House of Lords" of

The photographic essay by Karl Haupt with the title "911- a Photo

Essay of Ground Zero", walks a fine, subtle line between the

"symbolic-apocalyptic", as known from paintings, and the necessary

distance to the unimaginable suffering and fading hope by placing the heavy

weighing silence after the collapse into the center of the images.

This essay of black-and-white and almost monochrome-looking color photos

is beyond doubt one of the best photographic documentations on the catastrophe

in New York, it explicitly reflects that metaphysical level of total

destruction mainly ascribed to the myths of antiquity and biblical stories,

looming, vague and threatening. In Karl Haupt's essay this metaphysical level is

visible.

(Translated from the German original)

Exhibitions

Musée de l’Elysée, Museum for Photography, Lausanne, Switzerland – new york after New York

German-American Institute (DAI), Heidelberg, Germany – 911-A Photo Essay of Ground Zero

Hartwick College Gallery, Oneonta, NY, USA - Commemoration

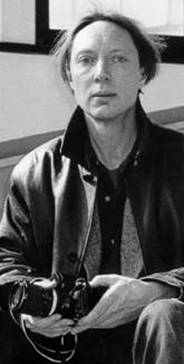

Photographer

Karl Haupt is

a filmmaker and photographer originally from Oneonta, N.Y., USA. As a son of a

US diplomat stationed in Germany, he lived in Cologne, where he studied art and

photography at the renowned Cologne Art Academy. Out of a need to add a certain

social dimension to his art, he went on to study social psychology at the

University of Cologne, where he also became involved in acting at the student

theatre and later in filmmaking.

Karl Haupt is

a filmmaker and photographer originally from Oneonta, N.Y., USA. As a son of a

US diplomat stationed in Germany, he lived in Cologne, where he studied art and

photography at the renowned Cologne Art Academy. Out of a need to add a certain

social dimension to his art, he went on to study social psychology at the

University of Cologne, where he also became involved in acting at the student

theatre and later in filmmaking.

His complete transition to

filmmaking cumulated into returning to New York, where enrolled in the New York

University Graduate Film School and earned his Master’s degree in film

directing.

He worked

several years in the New York and Los Angeles film industry, and made himself

somewhat of a name as a documentary filmmaker. Karl also was involved in

analogue music synthesis, and played in several New York and Boston post-punk

bands.

Later, he

moved to Paris, France, where he focused on film and music producing. Also, he

spent several years in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, where he shot several war

documentaries and where he was manager and producer to a well-known Yugoslav

singer and TV personality. Karl has known and documented a highly diverse mix

of Belgrade artists, paramilitaries, politicians, and Danube pirates and has

gained a certain expertise on wartime Yugoslavia during the time he spent

there.

Presently,

Karl Haupt is producing his feature film projects The

Voice of God, a romance set in Cologne, The Coast of Pearls, an

adventure story set in the United Arab Emirates, and Shadow Train, an epic WWII refugee train saga; based on his original

screenplays. At the same time he is organizing photography exhibitions of 911 - a Photo Essay of Ground Zero and developing other photo projects.

Contact:

Karl Haupt

tel. +49 221 240-2289

hauptka@yahoo.com

Copyright notice:

All photos by Karl Haupt copyright © Karl Haupt 2001 all

rights reserved

This material

may not be reproduced in any form without permission

Essay

Excerpt

Call 911 - the

nation-wide emergency phone number in the

9/11, as

September 11th is written as in the

The sheer

audacity, the brazenness of the attacks shocked so completely and left so many

millions slackjawed with astonishment that it is clear that the intended shock

impact went far beyond the planners' wildest expectations. It is safe to say

that never has any event ever grabbed the world's attention so completely than

9/11. It was modern transmission technology that put the world in the front

seat - hi-tech media screamed you-are-here-now - and riveted millions of

people to their TV sets, some for days. The impression these images made will

be with everyone who watched them, and we will remember

The

photographs of this essay were all taken during the night of

Order had

been rigorously applied to stave off chaos; the loose rubble on the fringes of

the site had already been removed, thus containing the disaster site to more or

less the original footprint of the larger

The military

authorities had banned all traffic and had kept everyone who wasn't directly

part of the emergency effort out of the Zone, as the military perimeter around

the WTC site was called. Thus all of

The immediate

vicinity of Ground Zero itself was only approachable from the south-east, since

a light wind was blowing the heavy smoke plume north-west, making that side of

the site unbearable without some sort of breathing mask. Southeast is

Few press

photographers had made it to this vantage point ever since

The evening

of the 13th September was a special moment in the annals of the

This moment

was also a cut-off point when the emergency management officials decided that

there was no hope of finding anyone alive in the ruins anymore. The specialists

listened one final time for any possible survivors; then they were called off

too. The helicopter gunships pulled out, the Secret Service finished their work

and left. For the first time the hectic activities at the site had came to a

halt. The ensuing silence was extraordinary.

This photo

essay attempts to describe this silence and the unreal, surreal atmosphere of Ground

Zero and the Zone. Although photojournalistic by nature, this photo essay is

different from the TV images we all have gotten used to. Although these photos

have documented the same reality, they have found a different way of describing

it. These are not photographs that shock; instead they invite the viewer to

look at what was in front of the camera lens at that particular, extraordinary

moment.

Ground Zero

was only lit by the on-site floodlights, all of

This night

was only a moment, but a particular moment plucked from a long recovery process

which changed rapidly with the circumstances, in the meanwhile almost all

traces of the

The

photographic challenge of this essay was to look beyond the shock imagery of

9/11 and describe Ground Zero and its surroundings from a different

perspective. To create images as distinct and unique as these it was necessary

to pay attention to the atmosphere of the area. It was important to develop a

sense of place and moment and to look beyond the shock and confusion, to see

more than trauma and chaos to convey a sense of presence, of being there.

Thus, these

photographs concentrate on the atmospheric; they focus on the strange, unreal

and unbelievable environment of the

This is

really war, like images of German cities at the end of World War II. Only the

primordial forces of the firmament should be allowed to wreak such destruction,

which then would be really God-given.

Sept. 13th - A large

building complex just across the West Side Highway from the

Further

inside the

The

passageways led through parts of still negotiable malls and arcades, previously

swank and elegant. Now filthy, torn up and drenched in dirty water, they served

as one of the main access routes for the volunteer workers from and to Ground

Zero.

Getting through these passageways required a flashlight and some caution,

since there was no electricity in the building complex. Site workers traversing

the passages shouted warnings to each other, pointing out potential hazards on

the dark and flooded floors, as well as twisted strips of framing material

hanging from the ceilings. The smoke was also quite bad and made it difficult

to see one's way; most people had either dust masks or had wet bandanas pulled

up over their faces.

On the far side of the

The harbor itself was now used to offload barges ferrying emergency

supplies from across the river from nearby

The arcades of one of the harbor-side restaurants had been set up as one

of these supply depots. Everything even remotely necessary was handed out -

construction boots, gas masks, gloves, goggles, batteries, hard hats,

flashlights, socks, clothing, tools and cigarettes, as well as hot meals,

sandwiches, coffee, water and soft drinks. In a way it resembled a cookout at a

military supply dump, except that the food, being donated by local restaurants,

had nothing military about it. In fact, the spare ribs and barbecue chicken

were highly praised by the site workers, who sat on the harbor-side stairs with

their food-laden plates or stood clustered in groups discussing the operation,

very garden party-like, belying the catastrophe just 100 yards away.

The night of the 13th September was also populated by medical

teams and emergency services. As activities were halted at Ground Zero, the

site workers headed towards the emergency shelters, some of them set up in the

nearby schools. One of them was in the

Several first aid stations were set up in the building, fortunately most

of the conceivable scenarios had not materialized - there were very few wounded

and injured to take care of, there were also few smoke-inhalation cases that

had to be treated. A few workers had cuts and bruises, also a sprained ankle

was bandaged, but mainly the medical staff was busy with applying eye drops to

those workers who had spent too much time in the acrid smoke plume and who were

suffering from minor eye irritations.

Supply deliveries had arrived without any problems and in great

abundance. Several distribution points handed out fresh clothing, shoes,

blankets, pillows and toiletries to the tired and weary. An auxiliary group had

even set up a massage area where they offered five-minute massages to anyone

who happened by. On the higher floors other field kitchens provided more hot

food, coffee, and snacks. Some rooms had TV sets set up, where the events of

the last two days could be watched. Late at night things settled down gradually

and the auxiliary groups now had a peaceful moment for themselves too; many had

been on duty for the last two days and now had the first moment to breathe

easily, knowing that the immediate pressure was off.

One of the team members, Shelah Desmond, a young nurse from

Desmond pointed out her ambulance from the window, one of several

hundred lined up along the West Side Highway, a 2-mile long line of ambulances

reaching all the way up to the

A policeman also was keenly aware of place, time, and the larger picture

when he asked for a spare roll of film. He had photographed all his police

buddies with "the pile" in the background, but ran out of film before

they could take a shot of him. So he needed a fresh roll, he explained, photos

for the family and back at the station. This need to record and document that

one had been there was equally important for two construction workers, who had

overheard the policeman and who made fun over his "almost missed

stardom". But they asked to have their picture taken and to have some

prints mailed to them so they could show their grandchildren. They needed proof

that they had worked at Ground Zero, for later times. A photograph would speak

more than words.

A huge electrical rainstorm swept over Manhattan that night, heavy

lightning illuminated the Zone in a most spectacular, apocalyptic and eerie

way. Most of the workers had found their way to one of the shelters, while

others still busy with moving heavy equipment were outfitted with raingear from

the supply depots. The heavy downpour only stopped during the course of the

following morning; much of the media had left, the spectators at the barriers

had gone home. The rain extinguished many of the fires that had been burning

inside the rubble; the smoke plume was greatly reduced. Most of the whitish

dust had been washed away; the Zone appeared completely different than just 16

hours before.